—Brett Leveridge An Interview with Michael PalinWhat was it about Hemingway that inspired this particular adventure? It was a mixture of admiration and humor, really. Admiration, because I think Hemingway was one of the pioneers of modern literature, whether you like it or not. Some of his work is dated now, but the way he was writing when he was writing in the 1920s was very brave and very different. I can remember discovering that when I was 16 years old at school. He was on the English literature syllabus, and he was the only author born since 1712 or something like that. You know, he was a modern writer. What really gelled the idea together was the idea of Hemingway as a traveler. He's not really known as a travel writer, and I think there's a tendency nowadays for travel writers to be put on one shelf and novelists on another. I think Hemingway absolutely qualifies as a travel writer. All his books are very, very carefully and precisely centered on the place he wants to write about. There are many different countries in the world, and they do create in me a real appetite to go and see these countries. I mean, if that isn't good travel writing, what is? So that was the idea for the series, to really make Hemingway's travels, basically. We called it an "adventure" to add a kind of irreverent flavor and to slightly up the rural edge to it. One could argue that Hemingway was not only ahead of his time as a writer but in that whole notion that a writer can forge a self-image and market himself. That's something that's done a lot now. He did it, I think, in a sort of slightly innocent way. He obviously had a lot to prove, to himself anyway. He had to prove that he could face almost any challenge and that he could understand things better than anybody else. This idea of the true gem. There's a very interesting comment by a guy called Morley Callahan who's a journalist in Toronto and knew Hemingway at the time. His quote was, about Hemingway, "He had to believe he knew, or he was lost." I think that shows the other side of Hemingway, sort of the dark, oppressive side, a streak that ran through his family and resulted in the suicide of many of his relations, including his father and two of his brothers and sisters. What makes his life interesting is it's a drama: Would he make it? Of course, he didn't make it in the end. Nowadays I'm really interested to know whether he'd survive the intensity of media examination. He could control what people thought of him more easily then than now, probably. Yes. He didn't really do that many interviews, hardly any television interviews. We've got footage of one that he did do, and it's very halting stuff. He's not comfortable at all. He didn't do a lot of press interviews, really. People would come out and do fairly worshipful, respectful things about him. One of my favorites is a bit by Lillian Ross for The New Yorker in 1950 called "Is That All, Gentlemen?" or something like that. She does a modern, kind of journalistic-style piece on him, following him around New York while he buys a coat in Abercrombie and Fitch and all that. It's very good. He didn't do much of that. How was the experience of tracing a famous man's footsteps through remote regions of the world different from your previous travel adventures? There was a different focus to the journey. The previous journeys, you tended to take two points and connect them, and look at what was happening in the countries where you went through to try and get the flavor of the places. This time there was obviously another element, which was Hemingway's presence there, the reason for the series. So there was a little bit of biography this time, which there wasn't before. You have to know a little bit about Hemingway. You have to look at it really through Hemingway's eyes. A lot of the activities that we saw—or that we chose to show—were judged by whether Hemingway had written about them or was involved with them. Then there were just moments that we did because they showed the excess of the modern commercialization of Hemingway, like Key West and the fridge magnets and T-shirts and look-alike competitions. One area we didn't go into, but it's fair game, is the Hemingway range of furniture. They brought out a whole new range of furniture for his 100th anniversary, and I think more people have probably sat on his sofa than read his books. In which locale did you feel most strongly the presence of Hemingway? Which was most familiar to you from his writings? North Michigan, definitely. He wrote a lot of stories about that area in North Michigan, where he went for vacation the first 18 years of his life. The Indian stories, the stories about relationships with the father, all the cabin stuff. That's barely changed. The stream where he fished, Horton Creek, where I went to try some fly-fishing. When you were out there on a canoe, you just couldn't see anything, not a telegraph wire, not even a plane going around. It was just like it must have been when he was there 85 years ago. So that seemed extraordinarily close to him. The other thing was his houses. Not Key West so much, because that's changed a lot inside. But the house in Havana, he handed that over to the Cuban government when he left in 1959 and just said, "Take the lot," because he couldn't take anything back to America. With the revolution, he was just glad to get out. He was sad to leave Cuba, but he just needed to move as quickly as possible. So you've got a house that looks as though he left it 15 minutes before. You've got the dining room table; you've got all his books still there on the bookshelves, the magazines he read. Even the bottles of drink, I think, are probably the same. The Cubans are desperately trying to look after his typewriter, his trophies on the walls. How great that they left it as it was, that they had that foresight. Yes, they look after it extremely well. In view of all the current talk about Cuba and relations between America and Cuba, I think it is worth remembering that the Cubans revere Hemingway, the American writer, as one of their own, really. They do consider him to be very important to Cuba. They look after his property there extraordinarily carefully. In the book you mention an auction that was announced; they were going to sell all Hemingway's possessions, but then it turned out just to be a hoax. Say it hadn't been a hoax: Which one possession—whether you know it exists or you just imagine that it might have—might you want to have? Ava Gardner's brassiere. It's just a wonderful thing. [laughs] I never knew anyone who thought this was a real thing, but there it was. We all know that Hemingway and Ava Gardner were very good friends, and there it was, this wonderful black bra. But the fact that it was in a frame, behind glass—I thought, That I have to have. So I was going to bid for that. Other stuff, I don't know. There were some wine bottles that he'd signed and I thought, That's rather nice. Because I like wine, and I like Hemingway. But we'd all have been fooled in the end. An extraordinary episode. When you visited bars that Hemingway used to frequent, did you feel any pressure to live up to his standards in the arena of tippling? I don't know how much of a drinker you are on your own, but I know he set a pretty high standard in that regard. I met someone the other day who remembers, when she was young, being in Europe, and she knew all these people like Irwin Shaw and many other prominent writers, and she said they all drank huge amounts. It is interesting how times have changed. Again, there was a sort of innocence that you could have a shot of scotch, one after another, and it'd have nothing to do with getting fat or putting on weight or being bad for your heart or your brain or cancer cells or anything like that. It was just something you did if you were a man. It's all changed now. I could never sit down in that bar and drink six double whiskies, as Hemingway would have done with no trouble at all. I just couldn't do it. I did try, but if I'd drunk as much as he did, we'd never have got the show going. The other thing, of course, is that Hemingway was only four years older than me when he shot himself, when everything caught up with him. And the drinking must have made the depression worse, and one thing led to another. He was in very bad shape when he was my age. So maybe I did the right thing. |

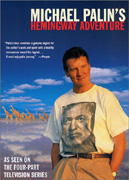

Michael Palin has distinguished himself in his post-Monty Python years as an adventurous, insightful, and brilliantly funny traveler. His latest voyage, chronicled in his new book, Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure, finds him following a lifelong interest in Ernest Hemingway to the places where the great author lived and wrote. I spoke to Palin in a cafe at his hotel in downtown Manhattan about following in Papa Hemingway's footsteps.

Michael Palin has distinguished himself in his post-Monty Python years as an adventurous, insightful, and brilliantly funny traveler. His latest voyage, chronicled in his new book, Michael Palin's Hemingway Adventure, finds him following a lifelong interest in Ernest Hemingway to the places where the great author lived and wrote. I spoke to Palin in a cafe at his hotel in downtown Manhattan about following in Papa Hemingway's footsteps.